Hello Lee,

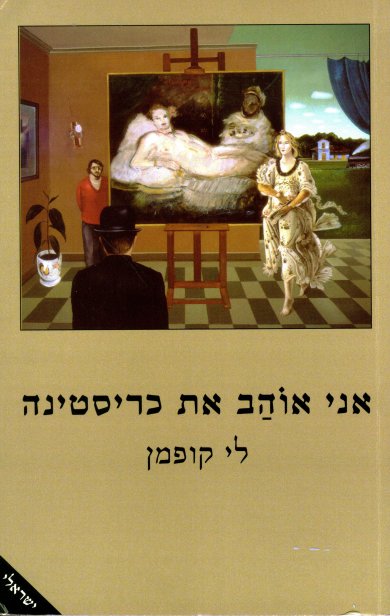

And I still remember so well how you’re feeling right now. It’s 2004 and you’re thirty and a year ago your third fiction book was published in Israel, but you haven’t lived there since the new Millennium began and the Internet still hasn’t taken over our lives, so you’ve no contact with your readers.

It’s as if your book has been sucked into a vacuum. Several people had warned you prior to your emigration that it’s impossible for a writer to change languages.

So who are you here, in your new home country? Who are you without your identity as an author? Without your literary milieu?

A paled version of yourself. A ghost.

Oh, I remember exactly how lost you feel…

You’re trying, though. Trying to resurrect your pre-immigration self. You came to Australia with the kind of English that allows you to place an order at McDonald’s, and that’s about it. So you stop reading in Hebrew, making English your first priority. You spend all your money on dictionaries, thesauruses and idiom books. You read all the time, as always, but now reading has become tedious, like watching movies in slow motion, because you’re checking every unknown-to-you word. Every word…

Initially you still write in Hebrew, then translate your works into bad English, then ask local friends to tidy your language up (how long will they keep doing you favours?). But soon English is crowding your mind, its words seeping straight onto your pages. You feel victorious for a week or so, then become preoccupied with the existential question all writers dread, but which torments you even more when you are an immigrant: what do I have to say and to whom? (And, of course, also: what publisher here would want to have anything to do with me?)

You don’t consider then, the way I’d now, that readers will always respond to a good story. That many of us grew up on Andersen’s fairy tales without being Danish, love Anna Karenina without ever seeing Russia. Perhaps your panic begins when you first attend a local writers’ group and are told that you can’t publish anything in Australia unless you write something about some small country towns and eucalypts and drifting clouds and sea.

Australians, well-meaning people explain to you, are possessed by their vast landscapes, perhaps because their grip on them, historically, is so fragile.

But you’re an urban creature. Your only experience of the Israeli countryside was a park in Tel-Aviv. Israel has so little space and your stories there unfolded in cities with traffic perpetually congested and residential buildings so dense they appeared to be climbing on top of each other. Your impressions of the Australian countryside weren’t as lyrical as the writers’ group implied was required, either. The roadside snooker pubs with their old jukeboxes inspired your writing more than the clouds. So what are you to do?

If only I could travel back to 2004 … to suggest to you that your outsider’s perception of your new country has a literary use. As Plutarch, who lived circa 100 AD, wrote:

‘the muses, it appears, called exile to their aid in perfecting for the ancients the finest and most esteemed of their writings’.

The Polish-English writer Joseph Conrad proved this theory right, bringing to England a sense of life’s strangeness that was lacking in Victorian fiction. And in his novel Lolita, the Russian-American author Vladimir Nabokov described the America of the 1950s like no one else had, highlighting its paradoxical mélange of sweet naivete and vulgarity. Wait a little longer and you, too, will dare to put your version of Australia, jukeboxes and all, in writing. And there will even be takers for your stories.

Changing your writing language can also help to hone your writer’s voice.

You’ll soon see that as a beginner you’ll have the opportunity to revive words long forgotten by locals and sometimes you’ll be able avoid the use of clichés through simply not knowing them. Moreover, inspired by your new language, eventually your voice will change its tune. From quite a tough, bravado-flavoured tone you’ll drift towards softer and dreamier sentences which you’ll like more. And this voice will speak to some local publishers and readers.

But wait, this isn’t all. V.S. Naipaul described people like himself, and yourself, as people ‘of no tribe’. There is plenty of angst in this position, in being the uprooted wanderer. But there is also something very humane in it. Being stripped of a country of origin, a mother tongue and a clear sense of belonging means what remains is a bare humanity which enables you to relate more to people of various tribes. And perhaps this will be soon what you’ll be trying to say in your works?

Happy writing,

Lee

Dr Lee Kofman is a Russian-born, Israeli-Australian novelist, short story writer, essayist, memoirist and former academic based in Melbourne. She is the author of three fiction books (published in Israel in Hebrew) and the memoir The Dangerous Bride (Melbourne University Press 2014). Lee is also the co-editor of Rebellious Daughters (Ventura Press, 2016), an anthology of personal essays by prominent Australian authors. Her short works have been widely published in Australia, USA, Canada, Israel, the UK and Scotland. Lee holds a PhD in social sciences and MA in creative writing, and is a mentor and teacher of writing. She is also a regular public speaker and panel moderator.

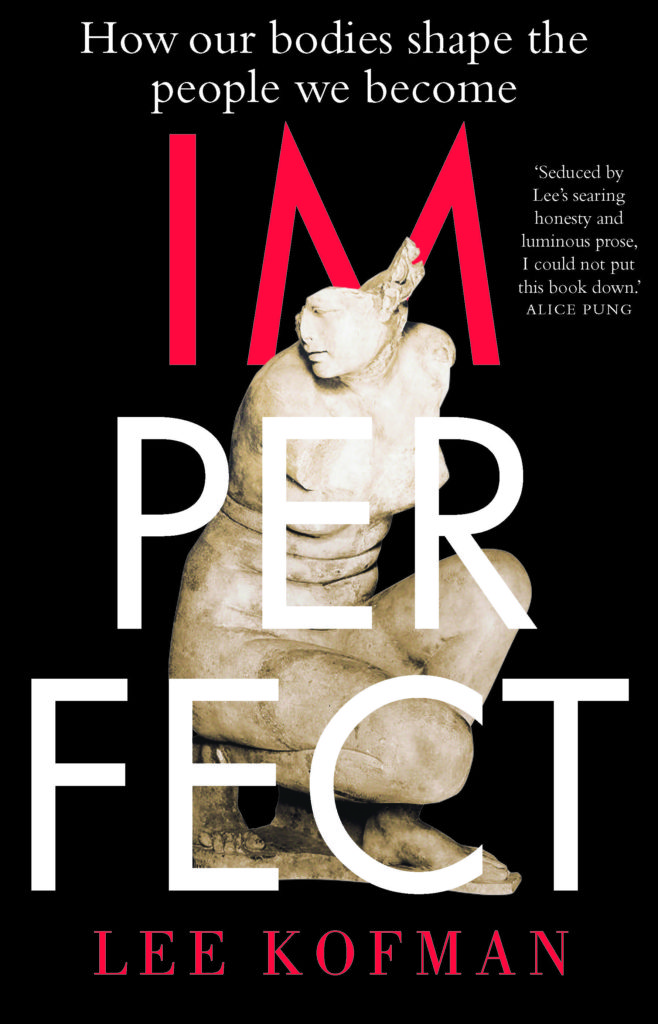

Her most recent book is Imperfect, a captivating mix of memoir and cultural critique, in which Kofman casts a questioning eye on the myths surrounding our conception of physical perfection and what it’s like to live in a body that deviates from the norm. She reveals the subtle ways we are all influenced by the bodies we inhabit, whether our differences are pronounced or noticeable only to ourselves. She talks to people of all shapes, sizes and configurations and takes a hard look at the way media and culture tell us how bodies should and shouldn’t be.

Illuminating, confronting and deeply personal, Imperfect challenges us all to consider how we exist in the world and how our bodies shape the people we become.

How does a website help rural fiction authors in Australia and NZ?

One Response

‘The roadside snooker pubs with their old jukeboxes inspired your writing more than the clouds.’ Me, too, and I get so sick of reading about the landscape!

I also agree that writers with English as a second (or third or fourth) language write gorgeously unique prose so different to the often boring and clichéd sentences that trip off our own native-speaking tongues.

Even bearing that in mind, though, Lee’s command of the English language is mind-blowingly superb. I’m in awe of her writing and her obvious intelligence. Can’t wait to read ‘Imperfect’!