Lia Weston is a fiction writer. Her debut novel, THE FORTUNES OF RUBY WHITE, was published by Simon & Schuster Australia in 2010. Her second novel, THOSE PLEASANT GIRLS, is due out with Pan Macmillan in May 2017. In between wrestling with plot points and procrastinating instead of writing her synopsis, Lia runs a bicycle shop with her husband Pete. Lia and Pete also own a German Shepherd called Kif, who has a fondness for raw pumpkin, and all the energy of a bean bag. Because she loves words so much (*grin*), I’ve split her Q & A into two. Part two is here.

Monique: Your novel Those Pleasant Girls has just been released. For those who haven’t been fortunate enough to read it yet, give us a little insight.

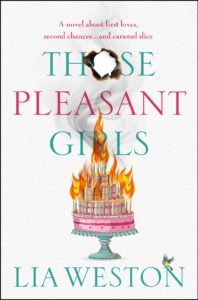

Lia: Those Pleasant Girls is the story of Evie Pleasant, who returns to the small country town she terrorised as a child. Reinvented as a 1950s pin-up, Evie’s divorce and impending poverty have made her desperate enough to try and rekindle her relationship with her former partner-in-crime and start again. She’s made a promise to herself: ‘No swearing. No drinking. No stealing. No fires.’ The town residents, however, have long memories; no-one is keen to have a vandalising, confectionary-shoplifting ex-local back, no matter how well they can bake a triple buttercream hazelnut sponge cake. With her reluctant Gothic gardening daughter in tow and her childhood sweetheart—now the local priest—in her sights, Evie has a job to do.

Monique: The book explores how motherhood impacts a woman’s identity. It really does – you become so and so’s mum … Where did this curiosity to explore the notion of sense of self come from?

Lia: I’ve always been fascinated by the way women are immediately pencilled as ‘a mother’, as if this is the thing that solely defines them. The sainted paradigm is the model that’s held up, and anything that falls short is viciously judged. (The media is particularly good at this—if a woman has transgressed in some way, her motherhood is usually the first thing they’ll mention to heighten the shock value.) Men don’t have this issue. It’s ridiculously unfair. So I’m interested in the way women are often shoehorned into particular moulds to be considered acceptable.

I’ve also watched with interest a few girlfriends’ transitions into motherhood, and how it’s affected their sense of self—as you’ve mentioned, becoming ‘so and so’s Mum’ and that’s it, which is hugely strange for women who have started businesses, finished university degrees, acquired high-level skillsets, and are independent and interesting people. Out of this came the idea of a woman who was a truant character as a child but was unexpectedly drawn into domestic life quite early, and found that she liked it. Would those truant characteristics come back at any point? What would happen if her serene, family-based world was suddenly shaken up? If so, how, and in what ways? Overall, I wanted to explore what factors influence our natural characters, and whether we can really change them or whether we just suppress them more or less successfully.

Monique: Do you have a favourite character in Those Pleasant Girls? Which character are you most like? Is there much of you in this book?

Lia: Ooh, this is a hard one, because it shifts during the writing process. Evie has my heart, because I put her through so much stuff, and I relate to her ability to make an ass of herself in front of people. Her daughter Mary is very much a teenage version of me, as far as her mopey bookworm tendencies go. I feel very protective towards both of them, because of their vulnerabilities, which I know so well. Mini D, however, is probably my favourite character, because he was so much fun to write; the words felt like they were just twinkling out of my fingers. You don’t get that effortlessness with every character (though the ones you have to really fight through often turn out to be the best) so I appreciate it whenever it happens.

There are degrees of me in this book; I grew up around churches, so I know the ins and outs of their particular politics quite well. I also love small country towns—such as Penola—so the book is a bit of a love letter to them. In addition, I’m an enthusiastic cook, which has been very handy for informing Evie’s background. However, Evie is very unlike me in several significant ways, which has felt quite different to when I was writing my first book, The Fortunes of Ruby White, where the heroine was really just me in disguise. It’s been a nice evolution to move away from that self-centred style of writing, which I think is potentially quite common for first-time novelists.

Monique: You’ve worked in a bookshop, studied psychology and explored alternative religions. How have all of these experiences helped you as a writer?

Lia: Any kind of retail work—and hospitality, too, for that matter—is gold for writers. Firstly, it teaches you patience and resilience. Secondly, it exposes you to a wide range of neuroses. You discover very quickly the disparity between what people say they want and what they actually want, which is very fertile ground for storytelling. Psychology was extremely useful for learning about the social structures of monkeys (seriously; I studied Hamadryas baboons for several months) and gave me a framework for certain schools of thought, but retail has actually been a much faster and more practical immersion in human behaviour. There’s far more material out in the real world!

Alternative religions have been a very interesting field, especially as someone who went to an Anglican school and had a serious bout of Jesus fever as a teenager. I was struck by the parallels between fringe and mainstream beliefs even though they look so disparate on the surface. The biggest lesson it taught me was that—regardless of to whom or what they pray—people are really just looking to be told that they’re OK and everything will be fine. This is the core of human nature, I guess, and also a large part of the reason why we read (and write)—to have that connection, that reassurance. I also did a great deal of study on cults, which was the springboard for The Fortunes of Ruby White. Psychological coercion continues to be a huge area of interest to me, and is also an underpinning theme of my third novel, which is coming out next year.

Monique: It’s clear from your website you have a talent for comedy. Well, I laughed. Several times. Do you think you’re funny? When you’re writing a comic scene, do you ever wonder if you’re as funny as you think or hope you are?

Lia: Thank you so much! It’s a total thrill to make someone laugh; it really never wears off. I like to think that I can conjure it up when I need to, but I’d not describe myself as ‘a funny person’. I actually find it strange when people refer to themselves that way, as if it’s a characteristic they’ve decided to tag themselves with in the hope of being more likeable. It’s like people who say they love music, as if this is a particularly unusual personality trait.

My writing has always had a comic bent, as that’s just how it tends to come out. (An early example is a poem I wrote for my dad when I was around eight, The Rainbow Bird. First verse: The rainbow bird/it lives in the sewer/Because of the smell/now there are fewer. At the time, I didn’t think it was particularly hilarious—I was merely making an observation about a fictional bird, after all—but Dad laughed until he cried.) I’ve found, however, that if I set out to write a comic scene—particularly one where the comedy comes from physicality rather than dialogue—I can’t do it. Instead, my comedy tends to leach out from the undertones of an otherwise serious scene, which I fortunately think is much more interesting. It’s something that I admire in writers like Austen and Dickens—the funniest things in their work (for me) are the little observations, the strange rituals of day-to-day incidents rather than big look-at-me scenes. I mean, the brilliant Douglas Adams—this is the structure of his work. So the scenes that I hope are funny are often not that funny, and the ones that seem straightforward often are. However, I learnt very early on that the more you try to work a joke, the flatter it falls. It’s like muffin batter: mix lightly and then leave it the hell alone.

Find out more about Lia’s writing process here.

How does a website help rural fiction authors in Australia and NZ?